Australia’s climate visa lottery model sets a troubling precedent

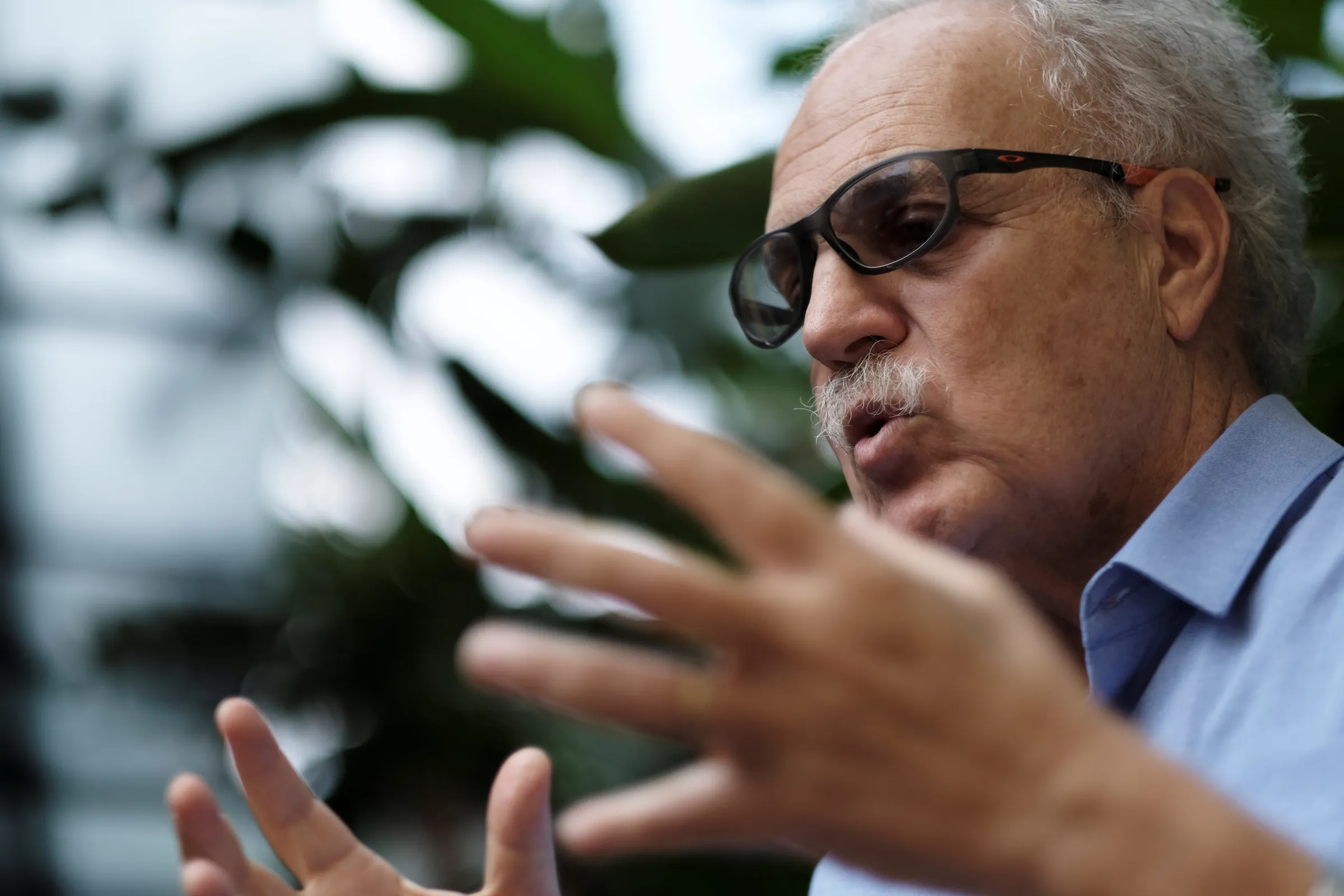

World Bank's president Ajay Banga views the impact of sea level rise in Funafuti, Tuvalu, September 6, 2024. A climate migration deal struck with Australia gives its population a pathway to move when the atoll nation becomes uninhabitable. REUTERS/Kirsty Needham

While lotteries can feel fair, they flatten complex realities. Climate change does not roll dice - and the vulnerable population of Tuvalu is at risk.

Yvonne Su is Associate Professor, Department of Equity Studies, at York University

A new era of climate migration is here, and Australia wants to be at the forefront. When the applications opened for a new 'climate visa’ to Australia, more than half of Tuvalu’s population of 10,643 applied for it. As the first country in the world to likely become uninhabitable due to climate change, Tuvalu is facing an existential crisis.

The offer? A mere 280 spots a year, selected by lottery. Billed as a landmark agreement and a forward-looking climate adaptation strategy, the scheme was hailed as generous, humanitarian and innovative. But it also sets a troubling precedent.

The impacts of climate change such as rising sea levels, intensifying storms, and collapsing ecosystems are not distributed randomly. They follow the contours of inequality, punishing those already marginalised by history, politics, and geography. Specifically, in the case of climate change, Pacific Islands account for just 0.02 per cent of global emissions yet they are the first and the most impacted by its consequences.

For comparison, the United States contributes 13% and China accounts for 31% of global CO2 emissions. And yet, increasingly, the response from wealthy nations have been to turn to the politics of survival into a game of chance.

Lotteries feel fair. They sidestep messy debates about who is most deserving, most at risk, or most responsible. But in doing so, they flatten complex realities. Climate change does not roll dice. It follows decades of underinvestment, colonially imposed infrastructures, and the exploitation of natural and human resources.

For Tuvalu, a small island nation whose carbon emissions are negligible but whose territory is disappearing into the sea, the climate crisis is not a random event. It is a result of choices made elsewhere.

The Australia-Tuvalu Falepili Union is, on the surface, a humanitarian gesture. But the mechanics reveal much more complicated political manoeuvring. Lotteries depoliticize climate displacement. They reduce it to a numbers game, where the line between inclusion and exclusion is drawn by chance, not accountability.

Governments love lotteries because they are administratively simple and rhetorically powerful. They appear egalitarian. Everyone gets a shot. In Tuvalu’s case, the odds are stark: a tiny fraction of applicants will be selected, and only a few hundred people will be eligible each year.

For a nation facing existential threats, the vast majority will remain behind, not because they are less vulnerable, but because they were not lucky.

It's also important to understand that the number of applications does not necessarily reflect a desire by the entire population to relocation. People applied because the cost of entry is low and the potential reward is high, a rational response to uncertainty. For most, applying was about creating an option, not making an immediate decision to leave.

This is especially true because under the agreement, visa holders apply for permanent residency in Australia, which includes the ability to live, work, study and travel freely between the two countries. As such, the high application rate can be seen as a strategic hedge against an unpredictable future.

This isn’t just the first-time randomness has entered policy design. The U.S. for example has long used visa lotteries, like its famous H-1B skilled worker visa program, where randomness is more acceptable because the system is designed to balance demand for skilled labour across sectors.

But when applied to climate displacement, where vulnerability is not the result of personal choices but systematic injustices, the same logic becomes ethnically fraught.

From school admissions to housing allocation, lotteries have been used to ration scarce resources when demand outstrips supply. But applying this logic to climate mobility is a profound shift. It suggests that adaptation is no longer a collective obligation but an individual gamble.

That in the face of global catastrophe brought on by the lifestyles and industries of wealthy countries, the best we can offer is a gamble with their lives and futures.

An aerial view of Funafuti, the most populous of nine atolls in Tuvalu, September 6, 2024. REUTERS/Kirsty Needham

An aerial view of Funafuti, the most populous of nine atolls in Tuvalu, September 6, 2024. REUTERS/Kirsty Needham

This is not to dismiss Tuvalu’s agency. Its leaders negotiated this deal with Australia in part to ensure continuity of nationhood, dignity for its people and the preservation of their culture. But the global framing matters, especially as the visa is seen as a model for other sinking islands and climate-vulnerable nations.

If climate lotteries become a best practice to pacify populations facing future displacement, we risk turning migration into a series of humanitarian sweepstakes. We ask the world’s most vulnerable to play fair while the game itself remains rigged. For the losers to accept their fate because luck didn’t fall in their favour.

There are more honest paths. Climate migration policy must reckon with history. It must recognize that vulnerability is not a random condition but a structural one. That means investing not only on orderly migration pathways but also in reparative justice, infrastructure support, and long-term planning rooted in partnership, not pity.

It also means resisting the temptation to mask hard choices with the appearance of neutrality. Random selection is not the same as fairness. It is a tool. And like any tool, it can be used to obscure as much as it reveals.

In the coming decades, more nations will confront the question Tuvalu faces today: How do we move with dignity in a world where staying is no longer viable? The answer cannot be left to chance.

Any views expressed in this opinion piece are those of the author and not of Context or the şÚÁĎĚěĚĂ.

Tags

- Extreme weather

- Government aid

- Climate policy

- Climate inequality

- Migration

Go Deeper

Related

Latest on Context

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

Most Read

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5